By Steven Soderberg, Lorin Industries Inc.

By Steven Soderberg, Lorin Industries Inc.

Anodized aluminum offers a durable, beautiful, lightweight and cost-effective alternative to stainless steel and painted metals for a wide variety of applications in architecture, transportation and consumer goods.

But, like all materials, it has its limitations. When subjected to extreme levels of thermal and mechanical stress, the surface layer can exhibit signs of micro fracturing called “anodize crazing”. Several proven strategies can be employed

to minimize or eliminate crazing to ensure that anodized aluminum products maintain their high performance and long-lasting aesthetic appeal.

Benefits Of Anodized Aluminum

Raw aluminum material is exceptionally durable and versatile, and it is sixty percent lighter than competing metals like stainless steel and copper. Anodized aluminum is created through an electrochemical process in which the metal is immersed in a series

of tanks that clean, anodize, color, and seal.

The oxide layer is grown from the aluminum itself, rather than being painted on or applied, and therefore anodized aluminum is much more durable than coated materials and will never chip, flake, or peel. Moreover, anodized aluminum will never rust, patina,

or weather.

Anodized aluminum also has many aesthetic advantages. The surface can be anodized in a way that leaves either a matte or bright finish of nearly any desired color, and the appearance of gold, bronze, copper, stainless steel, zinc, and brass, can be matched

without the risk of weathering.

With its high strength-to-weight ratio, anodized aluminum has a lower overall cost per square foot while matching the visual effect of gold, bronze, copper, stainless steel, zinc, and brass. And because anodized aluminum is so much lighter than other

metal products, it costs considerably less to ship to a job site or manufacturing facility.

The process of anodizing aluminum is environmentally friendly and sustainable. After oxygen and silicon, aluminum is the third most plentiful element on earth, and it is the only metal that is 100% recyclable.

Anodize Crazing

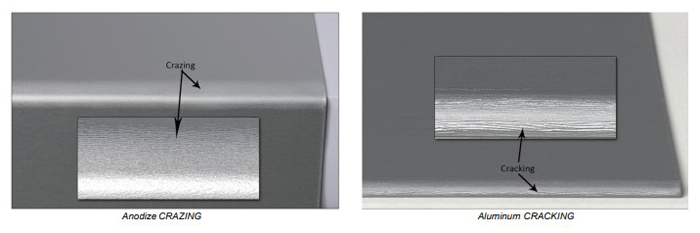

The oxide layer greatly enhances durability and appearance relative to the raw aluminum material. However, the difference in the material properties of the oxide layer versus the substrate also creates the conditions that can result in micro fracturing

in the surface layer. Specifically, the difference in the coefficient of thermal expansion between the oxide layer and the raw aluminum can facilitate thermal crazing, and the difference in elasticity and flexibility between the oxide layer and the

raw aluminum can facilitate mechanical crazing.

|

Under magnification, anodize crazing appears as very fine hairline scratches. Anodize crazing will not break through the oxide layer and into the base (raw) aluminum. This superficial “anodize crazing” is distinct from “anodize cracking”

that penetrates through the oxide layer and into the base aluminum as a result of more extreme thermal or mechanical stresses. When cracking does occur, the oxide layer has been separated from the base aluminum and no longer acts as a protective layer.

Thermal crazing occurs when the anodized aluminum is subjected to excessive heat. The coefficient of thermal expansion of the base aluminum is about five times greater than that of the aluminum oxide layer. As a result, the oxide layer will craze, and

in more extreme cases sometimes crack, because of these thermal stresses. Thermal crazing often forms in a pattern like a spider’s web.

Mechanical crazing occurs during forming and fabrication of an anodized aluminum part or flat rolled sheet. The oxide layer is very durable and about three times harder than the raw aluminum itself. As a result, when bending, stamping, roll-forming, cutting,

or drilling the anodized aluminum part or flat sheet, the oxide layer does not give and stretch commensurately to the raw aluminum substrate. For example, when forming a flat sheet into an 180° bend, the outside diameter will be longer (stretches

or expands) than the inside diameter (compresses or shrinks). The resulting mechanical crazing often takes on a frosted or dull appearance.

Minimizing Or Eliminating Crazing

The effects of crazing can be avoided or reduced in several ways:

Avoiding Thermal Crazing simply involves avoiding temperature extremes during the fabrication and operation of anodized aluminum products. The NASA-Goddard Space Flight Center published a technical paper in 1995 that an anodized aluminum part or sheet

should not be subjected to temperatures exceeding 320° F (160° C) in order to avoid thermal crazing.

Concealing Crazing involves making the crazing less visible to the naked eye. (In most situations crazing is just an aesthetic issue and does not affect the durability of the surface.) One method is to decrease the bend radius. The crazing is thereby

confined close to the edge and does not expand significantly onto the formed sheet or part, making the crazing less apparent to the naked eye. However, this approach will not work for some aluminum alloys and tempers that may require increasing the

bend radius to prevent cracking of the aluminum.

Another method is to decrease the thickness of the anodic layer to show less visible crazing. Thinner anodic layers are typically used for interior applications because UV exposure and environmental conditions are less critical. Reducing visible crazing

tends to be more important in indoor applications because the products are typically positioned at a close proximity to the viewer.

A third method is to use darker anodized colors. The oxide layer, being a crystalline structure, is not completely transparent, but rather is translucent, meaning it refracts light more than reflects light. The light passing through the aluminum oxide

layer is bent when it enters and reaches the base aluminum. It then bends again when it leaves the aluminum oxide layer. Because light travels at different speeds, we will see an image (crazing) that appears to change or take on a different shape.

Therefore, the glimmering (crazing) oxide layer is more apparent on lighter colors because lighter colors reflect more light than darker colors which absorb more light.

Anodized Aluminum Shines

By refracting light, the anodic layer creates a dynamic visual effect, thus making the aluminum come alive. Unlike painted metal, anodized aluminum is not flat, static, or one dimensional. Depending on the angle from which it is viewed, it can achieve

differing looks due to variables such as the amount of light, time of day, or even the time of year.

Whether you’re creating impressive buildings and structures, artwork, the latest line of luxury vehicles, or high-end appliances, anodized aluminum can be a beautiful part of your project or product. The anodizing process is eco-friendly and produces

a finish with unparalleled and dynamic beauty, longevity, and durability.